Prophecies and Promises: Christ, the bridegroom, and the women at the cross - Triduum 2025

A reflection on the women who stayed at the cross, in three parts.

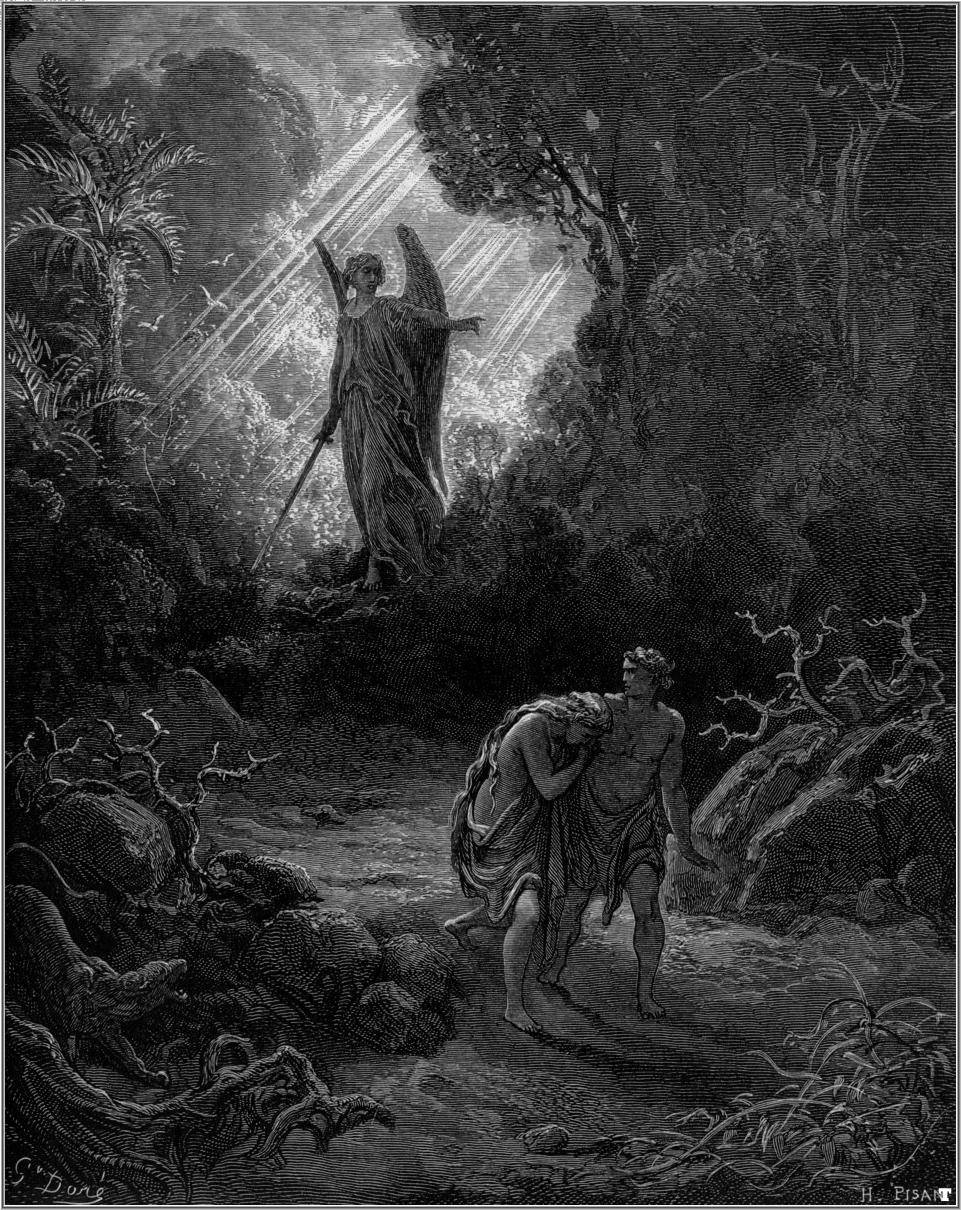

Image generated by Dall-E

Gethsemane

With one final breath while he hung from the cross, Jesus cried out over the earth and died. And women looked on, their eyes gazing on the crucified, themselves transfixed on something older than humanity itself. This is the story that we find in Mark’s account of the death of Jesus.

We have heard it well and often that Jesus is the new Adam, and that his crucifixion and resurrection are intimately bound up with the story of how man fell from grace in the Garden of Eden. So this year, in this Lenten reflection, I would like us to meditate together upon the story of the fall, the promises that were made, and the faithfulness of our God.

To be sure, there is a love story at play in the history of salvation, and the first protagonist, if we listen carefully – and perhaps much to our surprise – is not Adam, but Eve, the woman. If you ask yourself – or anyone else, for that matter – to account for where Adam was when Eve ate of the fruit of the forbidden tree, the likely answer is that he was somewhere else in the Garden. In fact, in our popular imagination, it is very likely that we imagine Eve alone at the tree with the serpent, and that after eating of the fruit she brought it to Adam. This is not the case.

In Genesis 3:6, we are told that the woman, after conversing with the serpent and delighting in the forbidden tree, ate its fruit and gave it to her husband, “who was with her.” Adam was also at the tree with Eve. He listened as the serpent lied, and he kept silent as he let Eve eat of the fruit first, only then eating of it after. But why is this important? What does this tell us about their relationship—and more importantly, about ourselves?

To answer these questions, we must first consider another garden, many centuries later. Indeed, everything in salvation history seems to lead us back to this original scene, but we must pause briefly to recall another pivotal moment. Fast-forward now to around 33 AD, when an itinerant Jewish preacher named Jesus and his circle of close friends found themselves at the heart of a political storm.

You see, the Jewish people have been waiting for their Messiah – the anointed one – to save them from their bondage. Over and over again, in fact, they have waited for the Lord to send them the Messiah who would once and for all restore Israel to its glory. Through exile, occupation, and oppression, God had sent many anointed ones, kings and judges, to help His children, but again and again there would be another oppressor who would rule over them.

In the first century, that occupant and oppressor was Rome. But this time, their king was not sent by God, but appointed by Rome itself: Herod, a supposed Jew of questionable lineage whose sole purpose was to keep the peace in Judea during this time of the great Pax Romana. Yet, the Jews of the time knew all too well that the peace the Romans offered came at a cost: it came at the cost of servitude, surveillance, taxes, and even violence and death. To be sure: Israel was not free.

Tensions were high: terrorist groups of fundamentalist Jews emerged whose purpose was to bring about the reign of the one true Messiah even by means of violence; sects of religious elders and leaders struggled for power over what it meant to truly observe the law of Moses; kings, like Herod, sought to ensure their reign at the hands of Rome; and the people, the everyday people – artisans, farmers, fishermen, innkeeps, and more – found themselves just hoping for better days ahead.

Amidst all of this comes Jesus, a Nazarene, son of a carpenter: a man who was as ordinary as one can be. For three years, he spends time preaching in Galilee, proclaiming a new kingdom, one unlike the kingdoms that this world knows: one of peace. He calls together a rag-tag group of twelve men, and gathers together others who fashion themselves as his disciples along the way. So alluring was this man who performed miracles for the lowly, the sick, and the outcast, and who preached a vision of hope for them that of their own will they came to call him Rabbi, teacher.

The Twelve, and the rest, would follow him wherever he went. So beloved was he to them, that they obeyed his every wish, and held on to his every word. So, when on that third year they entered into Jerusalem to celebrate the Passover – after the poor and radically loving Jesus disrupted all of those parties who were vying for power in this time of Roman occupation – it was no surprise that Peter, the first among them, when Jesus had told them at table that he would soon not be with them, declared, “I will lay down my life for you.” (John 13:37, New International Version)

Famously, Jesus admonishes him, “Very truly I tell you, before the rooster crows, you will disown me three times!” (John 13:38)

I will not recount the story – if you do not know it, I urge you to read the Passion in all four Gospels for a full account – but to summarize: shortly thereafter, after having agonized in the garden of Gethsemane, Jesus is arrested, having been betrayed by Judas, one of The Twelve. He is questioned by the chief priest and elders who find him guilty, then by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, who with too many crucifixions on record than the emperor would like, finds Jesus not guilty. The Jews however, having been riled up by their religious leaders, were not appeased. PIlate, who already had three crucifixions to be set, strategically used the tradition of releasing a prisoner to them on the eve of the Passover feast. He offers them Barrabas – a zealot (one of those violent fundamentalists) whose name literally translates to “son of the father” – or Jesus. Famously, and with biblical proportions of irony, the crowd demands the release of Barrabas, the political extremist whose very name claims to be the son of God. (John 18:40) With the same breath, regarding Jesus, who finds himself in this position after the elders themselves decided that he had called himself the son of God, the crowd demands, “Crucify him!” (John 19: 6,15)

To backtrack a bit, as we recalled this past Sunday, Palm Sunday, we remember that Jesus was welcomed with Hosannas upon his entry through the eastern gate of Jerusalem. This miracle worker who preached that the kingdom of God was at hand, to them, must surely be the long awaited Messiah who would free them from Rome and restore the glory and sovereignty of Israel!

How then, just a few days later, do we find this same crowd jeering at him, and demanding his death? Shortly put: this Messiah offered them a peace that was not of this world: a peace that is despite suffering, and not a peace that comes without it.

So, when Jesus is arrested, in fear of being caught up with this suffering as well (were the crowds at all right? Was Jesus not the Messiah?), the disciples scatter from him (Matthew 26:56), and Peter does deny his friendship with Jesus three times (John 18: 17, 25-26).

It is of note, however, that the women are not mentioned here, especially in Matthew’s account of the scattering of the disciples. But the women, who are notably silent in this story, interestingly resurface at the cross in all four of the gospel accounts of Jesus’ death.

2. Eden

Noticeably absent from Jesus’ suffering in the garden of Gethsemane are the women who followed Jesus around during his ministry. In this garden where Jesus’ sweat soaked the earth in his agony, no women are mentioned. To the biblically minded, one may be able to recognize something harkening back to a more ancient garden, and a more ancient story, where there was in fact, another woman.

In Genesis 3, we are told of how the first man and first woman ushered in the era of human short-coming. The story goes, of course, that after the creation of the world and its flora and fauna, God made man and gave him permission to enjoy all of creation for himself, such that he may name all of the animals, and eat of all the earth’s fruit, with the exception of one: the fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Then, looking at man in his estate, God decided that he would make for him an ezer kenegdo, a worthy helper. So, out of man’s side, he took a rib and fashioned from it woman to be his companion, his strength, and his assistance.

So much is to be said about this fruit, and what it says about a biblical cosmology, but I want to skip ahead to the scene at the tree where the notorious serpent in the garden tricks Eve into eating the fruit. Again, the story is familiar: the serpent begins the conversation and says to the woman – using deceitful language, already misconstruing the Lord’s instruction – “Did God really say, ‘You must not eat from any tree in the garden’?” (Genesis 3:1)

The woman responds in earnest, ““We may eat fruit from the trees in the garden, but God did say, ‘You must not eat fruit from the tree that is in the middle of the garden, and you must not touch it, or you will die.’” (Genesis 3:2-3)

The serpent then goes on to speak with its forked tongue first a lie and then a truth: “You will not certainly die, for God knows that when you eat from it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” (Genesis 3:4-5)

In the following verses, after the scene of this conversation, the woman perhaps finds herself at this tree of forbidden fruit. She looks at it, sees that it is delightful, and knows that it is good for wisdom – a divine property, as the snake tells her – and eats of it. Then she gives some of it to the man, and he eats of it too. We then are told of how God finds them in their guilt, interrogates them, and then deals with their disobedience. I will get to that shortly, but first, I want to turn our attention to a detail that I have been meditating on over the past year.

In Genesis 3:6, when the woman eats of the fruit, and gives it to her husband, a particular detail is mentioned. The text reads:

When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom, she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it.

“She gave some to her husband, who was with her.”

The man was at the tree. The man was at the tree with the woman when she took the fruit and ate it. He probably had no knowledge of the conversation she had prior with the serpent. All he had regarding this fruit was first hand knowledge from the Lord himself that he was not to eat of the fruit or touch it, lest he die. There is so much to be speculated about whether or not this injunction applied also to the woman, or how she even came to know about this instruction regarding the fruit of this tree. But what we do know for certain is that the man heard it from God himself, and here he was, watching the woman – who God gave to him as a gift to assist him in this life, worthy because he came from his very own flesh – eat of a fruit that very well could kill her. And when it doesn’t, he too eats of it.

Consider carefully the man's actions: he watched as his wife ate the fruit, fully aware it might have caused her death. Only after he saw that she survived did he partake himself. Such an action represents not just betrayal—breaking the bond between husband and wife—but profound ingratitude toward God. After all, it was God who gave this woman to him as a gift who was worthy to be called ezer, a word that is elsewhere used to describe God as man’s true help.

From this perspective, I offer that we consider that when God speaks to the woman, God’s response is not to declare punishments or “curses,” as most translations of the text would call them, but rather medicinal declarations meant to heal something that was fundamentally broken by this act. In Genesis 3:16, the Lord tells her that childbirth will be painful: a warning because she now possesses knowledge not only of what is good, but of what is bad. He tells her that she will be bound by desire to her husband: to repair the rupture that he had caused. And he tells her that the man will rule over her (when rulership is understood as bearing the burden of responsibility for another), because if he was unable to care for her as a gift of God from his own volition, he will do so as a matter of obedience to God’s will, and thereby under the pain of sin. The Lord here warns the woman of what pain will come, he repairs the damage sewn between her and her source, and then binds the man to protect her, to teach man obedience and gratitude, but also as a penance for having let the woman be endangered.

God then turns to the man and tells him, among other things, that, “by the sweat of your brow, you will eat your food until you return to the ground.” (Genesis 3:19) That is to say, that he will labor in agony until his death to repay this debt.

Lastly, I want us to remember that before God spoke to the woman or the man, he spoke to the serpent, pronouncing over it both a curse (Genesis 3:14), and a promise: “And I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers.” (Genesis 3:15).

Shortly after all of this, the man and the woman, now known as Adam and Eve, were expelled from the garden, with only the hope of promises to make any of this better.

3. Calvary

The place of the skull. Calvary. This is where we are now. Jesus’ work is now nearing completion. After having been accused, tried, flogged, and humiliated, Jesus carries his cross to its final place, where he is hung from it and left to die.

On the way there, while the men scattered, we find that Jesus is met by women who have followed him this entire way. We are told in Luke 23:27-31:

A large number of people followed him, including women who mourned and wailed for him. Jesus turned and said to them, “Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me; weep for yourselves and for your children. For the time will come when you will say, ‘Blessed are the childless women, the wombs that never bore and the breasts that never nursed!’ Then

“‘they will say to the mountains, “Fall on us!”

and to the hills, “Cover us!”’

For if people do these things when the tree is green, what will happen when it is dry?”

Jesus does something interesting here. First, take note of this explicit attention paid to the women who follow him. This was important enough of an encounter that the evangelist found it necessary to note it in this climactic scene of the story of Jesus. But also, note that Jesus is quoting the prophet Hosea here, the prophet of heartbreak and sorrow, who pleaded with Israel to return to God, their bridegroom and spouse, the one who made covenants with them.

Speaking to the women, using the words of the prophet, Jesus does something interesting here that is emblematic of the themes I am attempting to unravel in this reflection. What he does is remind the women of promises made long ago; that God’s promises are those of a groom to his bride, of a husband to his wife. These promises which are prefigured from the dawn of time in the garden.

When all was nearly lost, and even Jesus’ most beloved disciples – all men – betrayed and abandoned Him, the women stayed. The women followed. And as we see in all four of the Gospels (Matthew 27:55-56; Mark 15:40-41; Luke 23:49; John 19:23), as Jesus hung from the cross dying, as he spoke words from the prophets, calling to the present promises made long ago, the women stood there faithfully, weeping or watching, their souls hinged to the man Jesus, and their eyes transfixed to this tree which bore fruit which was altogether strange, and awful, but reminiscent of a primordial promise that persisted through the ages, deep in their bones, from the dawn of time in that first Garden where they had enjoyed the friendship of the Lord first, where they were first hurt and the Lord promised to heal them.

Mark puts it so poetically that the women were watching from a distance (Mark 15:40). The distance written into this story, inspired by the Spirit, calls to mind the distance between now and the primordial past. The women gazed into this distance, perhaps not knowing that what they witnessed here, what they followed to Calvary, was a promise being fulfilled.

Alone in the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus’ final work began, the sweat of his brow soaked the earth that he would soon return to. As he was led like a lamb to his slaughter, Jesus bore the weight of the scapegoat who would bear the sins of the world in order to make right what was undone long ago by disobedience and ingratitude for God’s gifts. As he hung on that cross, Jesus was himself the new fruit from the new tree of eternal life. In his last supper He gave us the covenant of His body so that we might eat of this new fruit and have eternal life, so that we might share in the oneness of God that we had forgone in the garden in exchange for knowledge of pleasure even if it came with the knowledge of pain. Hanging from the tree of the cross was the new ezer kenegdo – a man fashioned by God himself out of the body of the new Eve – the new help promised to woman long ago who would avenge the wrongs done to her. This is why we call the sacrament of Christ’s body and blood the Eucharist, the Thanksgiving, the covenant that is sealed with gratitude which we had owed since the first sin of man.

What the women at the cross should be for us is the reflection of the faithfulness of God and his promises. May we, Christ’s church, and his bridegroom, hold steadfast to his promises, for they are eternal, and they are good. For the same Jesus who hung on the cross is the same Jesus who rose from the dead, and the same Jesus who would later ascend into the heavens is the same Jesus who will return to take us to His father’s mansion, where He, our bridegroom has prepared rooms which He had promised to us.

In this world of suffering, where we are often at the hands of those who oppress us longing for relief from one Messiah or another, no matter how long we must wait, let us remember that the Lord’s Word is his bond. His Word is good, and so are His promises.

+

Holy Mary, the Theotokos, and the women who stayed at the cross: pray for us that we might remain faithful like our God. Amen.

+

A special thanks to Dr. Abi Doukhan and Dr. Anthony Malagon for musing me over the past several months as I put these pieces together.