On Vocation and the Sublime: Mysticism and Pneumatics for a Modernity in Crisis

The Calling of Saint Matthew, by Caravaggio

“Jesus said to them, ‘It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.’”

Those of us familiar with the Christian gospels know very well the adage quoted in the epigraph of this essay. Cited frequently among liberal and progressive circles, the admonition that Christ ate with and did favors for tax collectors, prostitutes, and the rest of despised in his community often serve as an attempt to remind others to love those who fail our own ideals in the same fashion that Christ did. It is, of course, the case that Jesus did in fact instruct his followers to love one another, and to treat even the least among them as one of their own. Though this is not a novel idea born from Christian instruction and similar admonitions are scattered throughout the Old Testament, Jesus did do something perhaps explicitly unique in his care for the destitute and despised. Not only did he show mercy, compassion, and hospitality to these individuals, he also called them to share in his ministry.

By no means do I consider myself a theologian. Aside from four years in minor seminary while in high school, my area of theological expertise is significantly broader than it is deep, so I will not pretend to be an expert by any means on the historical, anthropological, or philological aspects of Scripture. It is also not the intention of this essay to be ‘religious’ by any means, but rather to use biblical narrative as something of philosophical import, or rather illustrative of some greater moral point about responsibility and tragedy.

Arguably, in any experience of a Catholic seminary formation, one is bound to encounter a replica of Carravagio’s “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” which depicts a renaissance imagining of the tax collector’s call to apostleship. Allow me to stress that at least in its scriptural context, the tax collector was a despised individual because these taxes were collected as tribute for the Roman occupants who ruled over them. Of course taxes subsidized the Roman empire’s efforts to build up where they had put down their roots, but these unwanted lords were another oppressor in the Jewish history of subjugation. While the Temple tax – or what we today might call a tithe – was what helped sustain and provide resources and public services for the community, the additional Roman tax was not only an undesired debt, but one which also served to undermine the self-sufficiency of the Jewish community.

So more despised than a Roman tax collector is Levi or Matthew, a Jew who made a living from taking from his own. If there is any such thing as a sin against one’s community, to be a tax collector and a Jew was horrifically despicable. Yet, Jesus saw this man sitting at a tax stall, and called him to follow him. The Gospel according to Mark says that he left his belongings and went with Jesus.

There are perhaps two major moral lessons to be picked up from this bit. The first is the idea that the way out of the injustices we find ourselves in is often to take on responsibility for those who are wronged by those same injustices. The second is that to bear that responsibility often means taking courage and leaving everything behind.

In March of this year, Dr. Cornel West – a prophetic voice to say the least – gave a series of talks to the graduate philosophy students and then to a public audience at The New School. The title of that last lecture was, “Philosophy In Our Time of Imperial Decay.” The talk was a summation of the two prior lectures that he had given to the graduate students, and while much was said, the message to take home from the talk was that – especially in a time of national tragedy, whether momentary or ongoing, the latter of which signals a sense of decay – philosophy could, if not should, be understood as ‘vocation.’

The general line of thought that Dr. West made in this regard, and perhaps much more succinctly in one of the private talks prior, was that vocation – ‘being called’ – meant to recognize a need and to be compelled to do something about it. Very simply put, vocation, then, can be thought of as responsibility.

Yet the word ‘vocation,’ carries baggage that signals something else that goes beyond mere responsibility. I might postulate that vocation, as distinct from responsibility, entails a sense transcendence, a responsibility that doesn’t pose itself as a problem to be solved, as in “there is a problem, and we must figure out how to solve it,” but rather something more to-the-point, immediate, and imperative: “do something, anything!”

Emmanuel Levinas, the Jewish-Lithuanian philosopher who was notably taken up seriously by French Catholic leftists who were his contemporaries, offers us an ethical language to describe the immediacy of this responsibility. In his lecture, “Substitution,” [1] that eventually served as the “centerpiece” [2] of his second major work, Otherwise than Being, he writes: “The oneself is a responsibility for the freedom of others.” [3]

For a while, I struggled with trying to understand what that meant exactly. Much of the writing that happens after Totality and Infinity often seems obscure and hard to decipher, using the language of sacrifice that is for the biblically attuned ear deeply resonant with temple laws regarding sacrifice and sin, laid out in Leviticus and Deuteronomy. Putting this together with the phenomenological account of the “oneself” that Levinas gives throughout his career, the sentence can be understood that the very essence of human being is a responsibility for another.

For Levinas, the embeddedness of the human being is one that is, as a matter of fact, always-already one that is subject or beholden to others who impinge upon our freedom. This is the simple fact of human being that is characteristic of Levinasian phenomenology. Yet, as is the case with Levinas, phenomenological accounts mean nothing unless they work in some fashion towards an ethical end, and so the language to describe this primal responsibility, for Levinas, is most adequately the language of sacrifice, substitution, and debt. [4] [5]

I have previously written that part of what might be called the Levinasian project was to get away from the intellectualizing culture of Western philosophy and to really rescue the wisdom of Hebrew philosophy and its attunement to something beyond reason. [6] For Levinas, then, this religious language that speaks to something more immediate and visceral does have philosophical import. It signals towards something of the transcendental that reveals itself in the responsibility for the other that precedes comprehension. This language of debt and guilt adequately mesh with the idea of vocation as a responsibility incurred prior to my knowing it. Levinas calls this phenomenon “election;” this chosenness to bear responsibility, to carry a burden before one even comprehends what that burden is. Over and over again, Levinas describes this as a “passivity more passive than all passivity,” [7] and as a persecution. The idea that Levinas drives home here with this language is that before I am able to respond in this responsibility, I am already and inescapably bound to it; and in fact, this responsibility constitutes the very essence of my subjectivity: “Responsibility for the other does not wait for the freedom of commitment to the other.” [8]

The imagery Levinas clearly picks up on is one of election that is familiar to the ‘chosenness’ of the Jewish people. As God chose the Jews, we find ourselves in a similar position in regards to the transcendental nature of the Other.

Circling back to the call of Matthew and superimposing this Levinasian-Hebraic paradigm to it, this election and responsibility is met in the verses with an immediate response: that he went and followed Jesus when Jesus elected him. (Matt. 9:9; Mark 2:14; Luke 5:27-28) The profundity of the Christian account of vocation as I am describing it here and in the call of the twelve apostles is that the apostles were chosen by someone who they probably did not immediately recognize as God, but rather someone who was very much like themselves, the son of a carpenter. Suspending our disbelief, the idea to pick up on here is that it is in the face of someone ordinary like us where the call of transcendence can be heard.

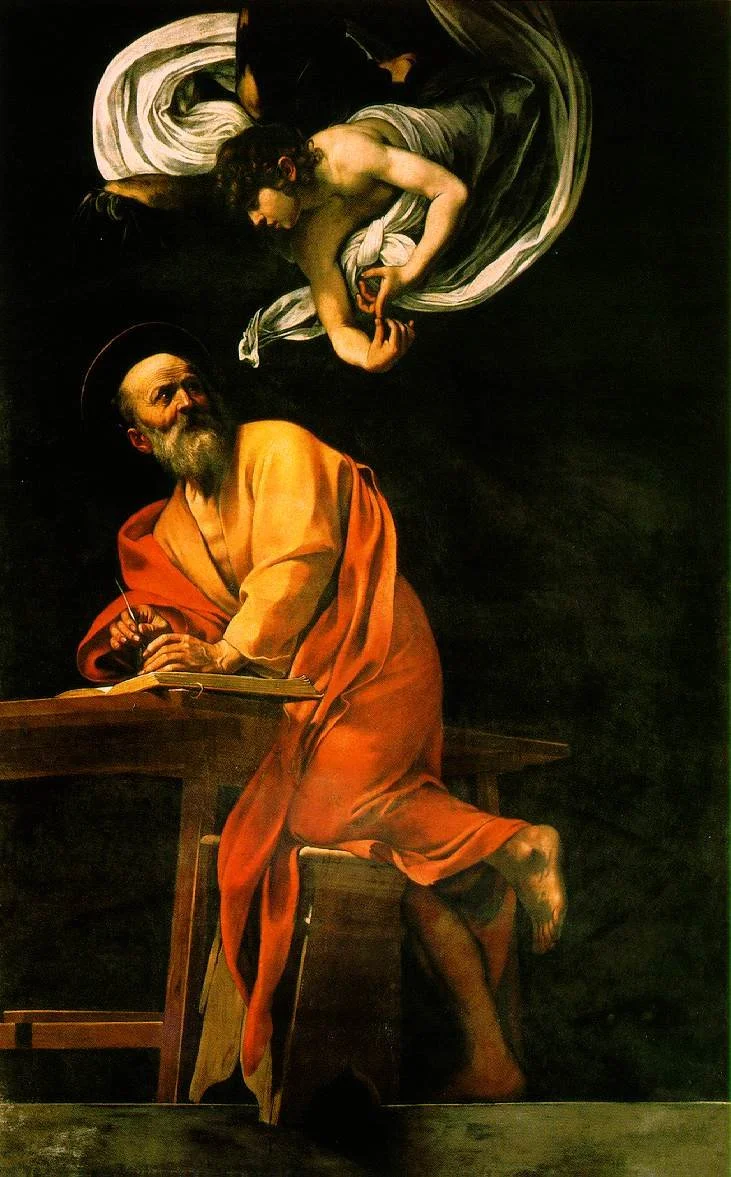

The Inspiration of Saint Matthew, by Caravaggio

What this Levinasian analysis of this Christian story can make sense of for all of us, I believe, is that in moments of terror, when we find ourselves and our neighbors facing tragedy, and in times of what may legitimately be called crisis, our ‘selves’ – spirit, soul, reason, minds, or what have you – we may feel moved beyond comprehension by a need that seems to emanate from no discernible site. This need comes from the incomprehensible transcendence of the Other, and it is more so terrifying in moments of tragedy and crisis precisely because absolute transcendence, as Edmund Burke aptly point out, overwhelms our sensibilities because of its sublime nature. Yet Reason is, pace Kant, capable of making a judgment of the overwhelming and often terrifying incomprehensibility of the sublime (whether that is nature or God). In that vein, Levinas similarly urges us to be responsive to the responsibility that captivates us. When we find ourselves mired in injustice, and so deeply buried in systems that overwhelm our capacity to break free from injustice, and systems that often have us complicit in them such that we find ourselves helpless or feeling unworthy, the way out is to bear the burden of responsibility for others.

For philosophers, it means thinking the hard things and writing them too. For doctors it means doing what is right even when it isn’t looked well upon. For lawyers it means standing up against the injustices of the law in pursuit of the law that emanates from somewhere higher. It means putting our reputations and livelihoods on the line. For those of us who know ourselves to be deeply spiritual, it is no coincidence that we all of late have felt the call deep in our skins. It is the particular and incomprehensible sense of the need of the Other that comes from an infinity beyond the faces we see and to which we are susceptible. This sensitivity is what one might call a “pre-propositional” [9] knowledge and it is not to be dismissed as unimportant or insignificant.

On the flip side, though, the call of Saint Matthew tells us something else. It tells us that this burden of responsibility comes at a cost: that we must leave everything behind in pursuit of this greater vocation. Simon Critchley had once reminded me in one of our conversations that Jesus had a novel way of thinking about ‘redemption,’ forgiveness, or absolution, and that each time he encountered someone who for whatever reason wished to express their gratitude for some miracle, favor, or whatever it might have been, their gratitude was accepted in the form of a call to give up everything and follow him. This is something that sits at the heart of Christian mysticism and asceticism; that the moral path is one of self-abjection. One need only look to the desert fathers as a mild case of this call to scarcity, or even to St. Francis of Assisi who was known to have carried a skull with him everywhere, that even while he wore sackcloth wished to be reminded that the greatest of abjections still was the pinnacle of Christian vocation.

While one may disagree with Levinas’ stance on morality — that there is an absolute passivity that is necessary for freedom such that one bears an infinite responsibility for the Other — I think what those objections often miss is that what Levinas fundamentally calls “critique,” that reveals the contradictions that ground our lives and perceptions. For Levinas, the ethical critique reveals that the moral way is the impossible way, yet still, it is the only way. As Simon had once said to me, perhaps the idea of morality Levinas has in mind is one of sainthood – even one of martyrdom.

However, I am not here to ask that we throw ourselves in front of gunfire or to sacrifice ourselves to some greater good – though maybe this is precisely what some find to be their true calling – but rather I invite us to understand that the formal structure of morality and the form of the Good is precisely the form of sacrifice. In all its meaninglessness and contradiction, we are called to make meaning by responding to the Call. There will be much to lose, and maybe nothing to gain. But what Levinas shows – and of what the saints are convinced – is that we must do something. We must be willing to risk something in pursuit of what often seems to be an unattainable end, and an elusive reward.

The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, by Caravaggio

NOTES

Emmanuel Levinas, “Substitution,” in Basic Philosophical Writings, ed. Adriaan T. Peperzak, Simon Critchley, and Robert Bernasconi. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996. pp. 79-95.

Ibid., p. 79

Ibid., p. 87

Simon Critchley, The Problem with Levinas, ed. Alexis Dianda. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015. p. 25

Dennis King Keenan, “Levinas On Resorting to the Ethical Language of Sacrifice,” in Question of Sacrifice. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005, pp. 74-88

Kevin Sue-A-Quan, “Levinas’ pessimism and the need for necessity.” Blog post, June 22, 2022.

Levinas, “Substitution.” “a passivity more passive still than all passivity…” (p. 90) “...the total passivity of the self,” and “an absolute passivity whose contraction is a movement…” (p. 89), etc.

Ibid., p. 89

J. Aaron Simmons and Jay McDaniel. “Levinas and Whitehead: Notes Toward a Conversation To Come,” in Process Studies, vol. 40, no. 1, 2011. p. 42

WORKS CITED

Critchley, Simon The Problem with Levinas, ed. Alexis Dianda. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Keenan, Dennis K. “Levinas On Resorting to the Ethical Language of Sacrifice,” in Question of Sacrifice. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005, pp. 74-88

Levinas, Emmanuel. “Substitution,” in Basic Philosophical Writings, ed. Adriaan T. Peperzak, Simon Critchley, and Robert Bernasconi. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996. pp. 79-95.

Simmons, J. Aaron, and Jay McDaniel. “Levinas and Whitehead: Notes Toward a Conversation To Come.” Process Studies, vol. 40, no. 1, 2011, pp. 25–53. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44799116. Accessed 25 Jun. 2022.

Sue-A-Quan, Kevin. “Levinas’ pessimism and the need for necessity.” Blog post, June 22, 2022. https://www.kevinsueaquan.com/blog/levinas-pessimism-and-the-need-for-necessity. Accessed June. 2022.