Being from the World: Levinas on the priority of freedom, and the cost of ethics

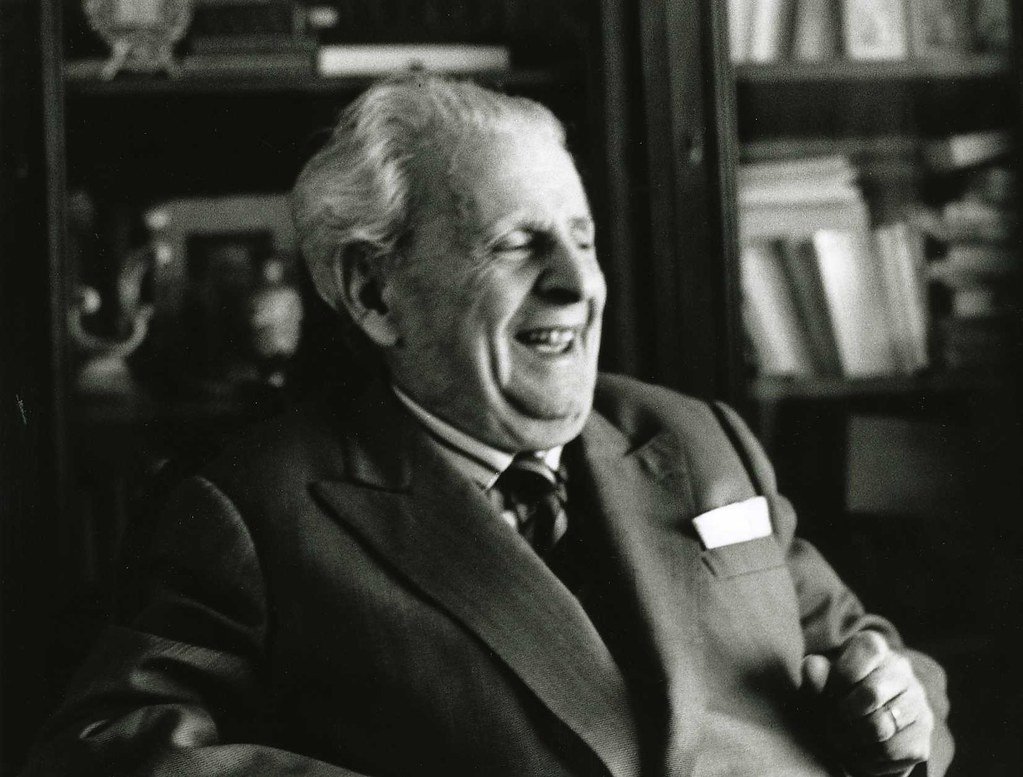

In Part II of his first major work, Totality and Infinity (TI), Emmanuel Levinas paints his image of the human not as a being that simply exists in the world prior to and separate from it, but rather as one which depends on the world in a way that is different from the concept of man’s relation to the world that was espoused earlier by Husserl and Heidegger who paint the image of man thrusted into the world, who must make sense of it in order to live, and who manipulates the things in the world for the purposes of sustaining his life. Both of these conceptions of human Being presume a conscious effort to imbibe the world, to use it as “tools,” as Levinas claims Heidegger would have it. (TI 110) Rather, man’s relationship with the world is one that already is embedded in a preconscious relationship with it. The world – perhaps best associated with some conception of nature – is what accomplishes man’s natural inclination to sustain himself. Human nature, for Levinas, is one of enjoyment and pleasure where the world serves no purpose for him, but rather is simply at his disposal. As Levinas concisely puts it, “The contents from which life lives are not always indispensable to it for the maintenance of that life… With them we die, and sometimes prefer to die rather than to be without them.” (TI 111)

To breathe, to eat, to drink are the very “pulsation of the I” (TI 113); the very heartbeat of life. For this survivor of the Holocaust, to situate man in an original state of enjoyment is to defy the philosophies of the modernity that Levinas believes played some hand in bringing about the horrors through which he lived. Man’s original state for him is one of enjoyment and of peace. “Pure being is ataraxy; happiness is its accomplishment.” (ibid.) Levinas strives to situate man as already free. Unlike his contemporaries and those who informed their thinking, like Spinoza, Kant, and Hegel, Levinas rejects the idea that man must fight for his freedom and attain happiness. Rather, Levinas makes the claim that man is already happy, and that he is already free.

I wonder just how important to Levinas it would be to cling to such a belief – that man, albeit thrown into the world, is in a state of peace with it, enjoying a level of mastery over the objects which fill it without needing to be conscious of the purposes they serve. Would to have believed in this primary situation have saved Europe from the evils of Nazi terror? Would only if the Germans understood that they did not need to seek their freedom nor reclaim their authenticity have the world perhaps not seen the annihilation of six million Jews and innumerable others?

If ethics is properly understood as a means for the good life, then this being from the world, or “living from…” as Levinas calls it – this prior state of bliss and mindless enjoyment – is the freedom to which we either must return, allow ourselves to return, or for which we must ensure protection.

It is from this “ontology” – though Levinas would take offense to this language – that Levinas’ ethics begins. That unlike the rest of the world, other people are not meant only for our sustenance, but are they who themselves need to be sustained. While Levinas would be enthused about a philosophy which decidedly positions others as necessary for the wellbeing and life of the self, he would also caution that unlike air, water, or the fruits of the Earth, other people have within themselves lives of their own, needs of their own, desires, wants, hopes and dreams of their own and who are, like us, worthy of protection and the insurance of the same freedom afforded to ourselves by our very nature. It is this unknowable interiority of the other which subjects us to a responsibility that asks us to skirt our freedom; to relinquish a tiny bit of our carefree abandon with the world to protect the needs of another.

It is on account of this interiority that escapes human mastery that Levinas makes the claim that the face of another, that the Other itself impinges upon our freedom and bears the dictum: Thou shall not kill. (TI 199) This negative injunction is a limit on human freedom, and it is this command which not only is the beginning of ethics for Levinas, but also the pinnacle of the philosophical import of his writings: to demonstrate the limits of human will and to insist that freedom is not the ultimate end of human existing, but rather its nature and source.

———

All citations from: Totality and Infinity by Emmanuel Levinas, translated by Alfonso Lingis. Duquesne University Press (1969)